Igor Domsac | 13 July 2022

(last update: August 10, 2022)

Psychoactive plants and fungi are becoming more well-known, and we are beginning to hear more about amphibians whose secretions are also able to alter consciousness. The toad known as “Bufo” is increasingly being talked about in the media and online forums. The Latin nomenclature of Bufo alvarius is often used to refer to a species of toad that produces large quantities of the psychoactive substance 5-MeO-DMT within its specialized skin glands, most prominently, its parotid glands. But this infamous amphibian goes by many other names, scientific or otherwise, which we will get into more detail about below.

Perhaps the name Kambô also rings a bell. Are these two amphibians equally psychoactive? In response to ongoing confusion in the world of consciousness-expanding fauna, this article offers a bit of clarity by delving deeper into the origin of this amphibology.1

The Many Monikers of “Bufo”

Let’s get straight to the point. The toad widely referred to as Bufo alvarius has a more accurate scientific name which is Incilius alvarius. I. alvarius is a species of amphibian belonging to the Bufonidae or “True Toad” family. Its habitat spans the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico. It is also known as the “Colorado River Toad” since it used to reside in the areas surrounding this infamous body of water. Another common name is the “Sonoran Desert Toad” because it is found in the Sonoran Desert region.2

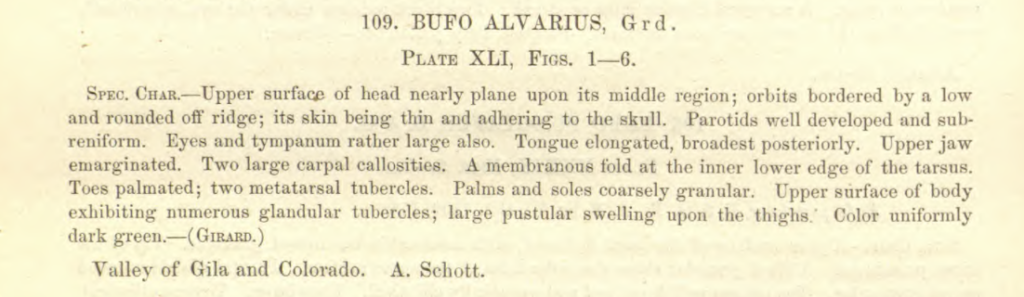

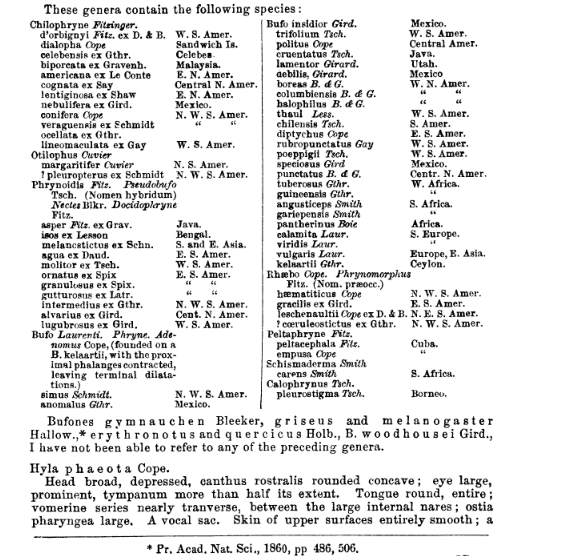

The first known reference to the term “Bufo” comes from the Roman poet Virgil in the 1st century B.C to refer to “a certain kind of poisonous terrestrial frog.”2 However, this species was first described in the scientific literature in 1859. Specifically, it was the French physician and zoologist Charles Frédéric Girard who named it Bufo alvarius.3

Source: https://webapps.fhsu.edu/ksherp/bibFiles/61.pdf

Source: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4059486.pdf

The toad was later given the Latin name Phrynoidis alvarius, but this was not widely accepted. Bufo was used to describe this species from 1859 until 2006, when Darrel R. Frost and colleagues changed it to Cranopsis alvaria. This Latin word — Cranopsis — has been used to classify various frogs, mollusks, and branchiopods. Later that year, the authors pointed out that this scientific name was inaccurate and proposed Ollotis as a replacement, calling the toad Ollotis alvaria.3

In 2009, Frost and colleagues decided that the genus Ollotis should be changed to Incilius, which graced us with the correct Incilius alvarius nomenclature used today.3 In 2011, Mendelson et al. integrated the past scientific names for the toad and made them synonymous with Incilius.4 Geography seems to define Incilius further, as these toads solely inhabit the southwestern USA and northern Mexico. Some have argued that Incilius should be considered a sub-genus of Bufo. For the time being, they are different genera.2,3 Incilius has now been broadly accepted and is commonly used in the scientific literature, although the psychedelic community has yet to catch up.

Although there are other species of toads that also contain bufotenin (such as Rhinella marina, Bufo bufo, or Bufo viridis), the secretions of the Sonoran Desert Toad (I. alvarius) “are the only ones containing 5-MeO-DMT, or 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine, among all known toad species.”5 This is because I. alvarius has a special enzyme (O-methyl transferase) that converts bufotenin into 5-MeO-DMT, a very potent psychoactive substance. The secretions can reach up to 5-15% of the total dry weight in the parotid glands, resulting in a considerable amount of 5-MeO-DMT. One Sonoran Desert Toad can produce up to 75 mg of this substance.5 Thus, I. alvarius produces the greatest number of psychoactive compounds and therefore is the most sought after by those looking for a psychedelic experience.

I. alvarius is of great cultural importance for the Yaqui peoples of the southern Sonoran Desert region. While this particular Indigenous group in the area where the toad resides has a longstanding kinship with the animal, smoking toad venom only became a practice in the 1980s. A spike in interest came when a widely distributed pamphlet — Bufo alvarius: The Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert by Albert Most — described the 5-MeO-DMT content of the toad’s secretions. These narratives have led to a modern practice of “smoking toad” that has become popular within the psychedelic community.

Smoking toad venom is an example of current practices that are not specifically rooted in the traditional Indigenous lineages where these animals live.6,7 The booming interest in the Sonoran Desert Toad as a source of 5-MeO-DMT is leading to increased pressure on the animals’ populations and ongoing sustainability concerns.5 Indigenous leaders have specifically asked for people not to collect or consume the Sonoran Desert Toad while populations are facing such threats. Synthetic 5-MeO-DMT is an alternative that doesn’t put pressure on the toad or its environment.

The toad generally hibernates in underground burrows. It resurfaces in the summer to breed in shallow ponds and streams which makes it vulnerable to being snatched from its habitat. According to Robert Villa, president of the Tucson Herpetological Society and a research associate with the University of Arizona’s Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill, “[t]oads offer those secretions in a defensive context, in a stressed and violent context. […] Ultimately, people are self-medicating at the expense of another creature.”8 This species is listed as threatened in certain states and believed to be extinct in others.

Kambô vs Incilius alvarius

Kambô, an Amazonian treefrog (Phyllomedusa bicolor), is also called “toad” (or sapo, in Spanish) when it actually isn’t one. This amphibian is also referred to as campu, acaté, Waxy-Monkey Treefrog, Giant Maki Frog, or the “jungle vaccine.” Kambô is a traditional medicine extracted from the skin secretions of P. bicolor. This nocturnal treefrog inhabits the Amazon and Orinoco basins of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.9

The recently deceased journalist Peter Gorman, author of the book Sapo In My Soul: The Matsés Frog Medicine, was given Kambô in 1986 by the Matses people, who called it “ordeal medicine.” Gorman was the first person to send samples to the USA for chemical analysis. His book tells the story of the Western world’s discovery of Kambô and aims to be a guide to working with the medicine.

Kambô and the Sonoran Desert Toad are not closely related species, nor do their secretions have the same properties. To compound the confusion, a common name for the Sonoran Desert Toad in Latin America is also sapo. The experiences produced by these animals’ skin secretions yield very different results.

While historically classified as a psychedelic, Kambô doesn’t create any hallucinatory or psychoactive effects. Over 15 Indigenous groups in the Amazon Basin have worked with the frog for generations to attain a deep cleansing of the body and soul.10,11 In comparison, parotid secretions of the Sonoran Desert Toad contain 5-MeO-DMT and bufotenin, which immediately induce strong psychedelic experiences when smoked.7 Since becoming more popular in psychedelic communities, demand for I. alvarius has led to significant pressure on their populations. Conservation issues have resulted in calls encouraging the use of synthetic 5-MeO-DMT instead.7

The routes of application with Kambô and I. alvarius are very different. Sonoran Desert Toad secretions are inhaled via smoking, whereas Kambô medicine is applied by making small burns on the skin with a stick. Kambô is then placed over the wound and its effects last between five and 20 minutes.12 The experience with I. alvarius also has a short duration of action, lasting a mere 10 to 20 minutes. However, “[g]iven the different routes of application, users do not usually confuse the two substances, although ceremonies combining the secretions of Kambô and Bufo alvarius [sic] have recently been proposed in Western psychedelic circles.”13

While Kambô isn’t currently facing the same sustainability pressures as the Sonoran Desert Toad, the rapid increase in interest has generated concern from those worried about the treefrog’s future. Environmental activists have called for research on the impact that over-harvesting and habitat security would have on the animal’s future population and the Indigenous populations who have traditionally worked with Kambô. Some people also express concern for the animal’s welfare, especially when its medicine is becoming more popular. As interest in Kambô expands, those gravitating toward its medicine should be aware of sourcing issues and the impact their choices may have on the treefrog, its habitat, and Indigenous communities.14

What Does the Research Say?

It is important to note that there is little information concerning the safety or effectiveness of practices involving the Sonoran Desert Toad or Kambô. In terms of 5-MeO-DMT, there is not much published. The currently available information comes from observational research, not controlled studies. Nevertheless, these observational studies have shown that 5-MeO-DMT led to significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression in about 80% of participants.15

Additionally, a couple of observational studies looked at veterans from the United States that completed treatment involving 5-MeO-DMT about 48 hours after ibogaine administration. Researchers found significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress, alcohol consumption, suicidal ideation, and cognitive decline associated with traumatic brain injury.15 A single inhalation of vapor from dried I. alvarius secretion in a naturalistic setting was found to be related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, a higher capacity for mindfulness, and a decrease in psychopathological symptoms.16

In terms of Kambô, a study published in 2018 showed that “[t]he administration of Kambo results in a symptom-complex resembling a transient anaphylactic shock.” However, it seems that this is not caused by the immune system overreacting to an allergen. It appears it is the pharmacological effect of bioactive neuropeptides likely acting in synergy with one another. Based on these findings, the author provided some recommendations in order to make Kambô rituals as safe as possible. Firstly, starting off with a small dose is important to see how the participant responds. In addition, Kambô’s efficiency depends on many factors, so the response to dosing can vary widely. The author noted that high doses may create severe adverse reactions that may require hospitalization.17

Another study reports that the acute psychological effects of Kambô are vastly different from classic psychedelics that act on serotonergic pathways. Researchers found that experiences with this medicine can result in increased energy, stamina, and mental clarity after the initial feelings of sickness and exhaustion subside. These findings support what anecdotal reports have described in the Kambô experience. In addition, “persisting effects were predominantly described as positive and pleasant, revealing high scores on measures of personal and spiritual significance.” The authors concluded that while the Kambô experience is unique, the transformative effects of working with it may be comparable to classic serotonergic psychedelics.18

Paving the Way for a Sustainable Future for Psychoactive Amphibians

One of the greatest benefits to those working with amphibian, botanical, or fungal medicine is when their personal growth positively influences the community. Both Kambô and the Sonoran Desert Toad are an integral part of the traditional communities that honour them. Therefore, it is essential that our quests for consciousness exploration do not decimate their existence. While more research is needed, these topics should be investigated with a high level of respect for these animals and their biocultures.

When discussing toads with medicinal or psychoactive properties, it is best to make a distinction between species in order to avoid misunderstandings and ensure ethical, safe practices. Because experiences with both Kambô and I. alvarius are becoming more frequently sought after, it is crucial for the psychedelic community to be aware of the impact these decisions have on the animals and their environment.

Timothy Harvey, director of Alvarius Research, works to provide scientific resources to enable the conservation of Incilius alvarius. He says that there is no research focusing on the genetic diversity and structure of the Sonoran Desert Toad.

“We can expect there to be potential for decline but the research has not been conducted,” he says. “Setting conservation priorities requires knowing where the most imperiled pockets of diversity exist.” He reports that their team is “willing to produce and publish a genome assembly, making it available to all researchers to work with – and to analyze genetic samples collected across the species range.”

There are also steps being taken to provide an alternative full-spectrum toad medicine via cell culture as opposed to sourcing it from the toad itself. This method is claimed to be the only way to reproduce a composition comparable to the animal in the lab. One company has reported they have successfully reproduced toad parotid glands and the world’s first known cell-based 5-MeO-DMT. This process recreates the basic cell structures that carry out the physiological processes of the organism.19

The Sapo Sagrado Conservation Initiative is a new organization formed out of concern for the future of the Sonoran Desert Toad and Kambô. They state, “both of these species face a very uncertain future, due to overcollection, habitat loss, insecticide use, and the impact of the fungal disease Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis. The Colorado River Toad and the Waxy Monkey Frog are both facing a variety of pressure including increased interest on the part of psychonauts in experiencing the effects of using the products, extracted unsustainably by the profit-minded.”

The organization reports this includes the wholesale collection of I. alvarius, even in protected areas such as Mexico. There are also unsustainable levels of collection in Arizona. In the case of P. bicolor, increasing numbers are being collected and offered in a ceremonial setting.20

Increased toad poaching and illegal transport across state borders is also occurring on the US-Mexico border.21 Joe Franke, a conservation biologist and herpetoculturist who is the founder of the initiative, warns: “Given the fact that there is anecdotal evidence that Mexican drug cartels are becoming involved in the international trade of sapo, people really should not buy it from anybody.”

Franke also reports that, “unless there is serious intervention, including captive breeding and wide availability of synthesized 5-MeO-DMT, this species could be in serious peril, particularly as monitoring is so poor on both sides of the border.”

Amphibians are some of the most endangered invertebrates on the planet. According to Amphibiaweb, “in just the last two decades there have been an alarming number of extinctions, nearly 168 species are believed to have gone extinct and over 43% more have populations that are declining.”21 The international community can take this opportunity to be well informed about their impact on animal medicine, their habitat, and the people that share the land with them. This will enable us to establish a long-lasting symbiotic relationship with our environment that can be enjoyed for generations to come.

As William Shakespeare said, “sweet is the fruit of adversity that, like the ugly and poisonous toad, bears on its head a precious jewel.”

Thank you to Anny Ortiz, Jim Rorabaugh, Timothy Harvey and Joe Franke for their input and feedback on this article.

References

- According to the Collins Dictionary, “double or doubtful meaning; ambiguity, esp. from uncertain grammatical construction,” and “an ambiguous phrase, proposition, etc.”

- Frost, D. R. (2017). Amphibian species of the world: an online reference. Version 6.0. Electronic Database. American Museum of Natural History, New York. Available online: http://research.amnh.org/herpetology/amphibia/index.html. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Pauly, G. B., Hillis, D. M., & Cannatella, D. C. (2009). Taxonomic freedom and the role of official lists of species names. Herpetologica, 65(2), 115-128.

- Mendelson III, J. R., Mulcahy, D. G., Williams, T. S., & Sites Jr, J. W. (2011). A phylogeny and evolutionary natural history of mesoamerican toads (Anura: Bufonidae: Incilius) based on morphology, life history, and molecular data. Zootaxa, 3138(1), 1-34.

- The International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service (ICEERS). (2019). Bufo Toad (Incilius alvarius): Basic Info. PsychePlants. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Cotina, Ali. (2018). Controversies Around the Toad Medicine. Chacruna. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- Liana, Lorna. (2019). Bufo Deaths & Fraud Involving Toad “Shamans” Octavio Rettig & Gerry Sandoval. Entheonation. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- Kutz, J. (2021). A hallucinogenic toad in peril. HighCountryNews, June 7, 2021. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- AmphibiaWeb. (2007). Phyllomedusa bicolor: Waxy-Monkey Treefrog. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Retrieved 4 Jul 2022.

- Coffaci, E. & Silva, F. (2018). New Urban Practices Around Kambô. Chacruna. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- The International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service (ICEERS). (2019). Kambô: Basic Info. PsychePlants. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- Schmidt, T. T., Reiche, S., Hage, C. L., Bermpohl, F., & Majić, T. (2020). Acute and subacute psychoactive effects of Kambô, the secretion of the Amazonian Giant Maki Frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor): retrospective reports. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-11.

- Davis, A. K., So, S., Lancelotta, R., Barsuglia, J. P., & Griffiths, R. R. (2019). 5-methoxy-N, N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) used in a naturalistic group setting is associated with unintended improvements in depression and anxiety. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 45(2), 161-169.

- Ribeiro, Filipe. (2021). The Challenges of Kambô Conservation. Chacruna. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- Mangini, P., Averill, L. A., & Davis, A. K. (2022). Psychedelic treatment for co-occurring alcohol misuse and post-traumatic stress symptoms among United States Special Operations Forces Veterans. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 5(3), 149-155.

- Uthaug, M. V., Lancelotta, R., van Oorsouw, K., et al. (2019). A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness-related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology, 236, 2653-2666.

- Hesselink, J. M. K. (2018). Kambo and its multitude of biological effects: adverse events or pharmacological effects. Int Arch Clin Pharmacol, 4, 17.

- Schmidt, T. T., Reiche, S., Hage, C. L., Bermpohl, F., & Majić, T. (2020). Acute and subacute psychoactive effects of Kambô, the secretion of the Amazonian Giant Maki Frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor): retrospective reports. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1-11.

- Carpenter, D. E. (2022). Scientists Create Cell-Based Psychedelic Toad Venom, a Potential 5-MeO-DMT “Bio-Factory”. Lucid News, February 8, 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Vinopal, L. The Rise of Kambo — A Toxic Frog Fluid Wellness Detox. MEL Magazine, April 2022. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- Rex, E. (2022). Could the Sonoran Desert Toad Cure Narcissism? Psychedelics Today, April 14, 2022. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- Oshiro, Julianne. (2021) Why Save Amphibians? Amphibiaweb. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

Photo by David Clode on Unsplash.

Categories:

NEWS

, PSYCHEPLANTS

, Others

, Incilius alvarius

, Kambô

Tags:

bufotenin

, 5-MeO-DMT

, Bufo alvarius

, kambô

, Incilius alvarius