Environmental activist Erika Oblak, who publishes her work under the name Isa Mea, spoke at the World Ayahuasca Conference 2019 on “Reciprocity and the Impact of Ayahuasca Tourism.”

Oblak, a Slovenian environmentalist, opened her talk by explaining that ayahuasca tourism must be understood within the more general context of tourism in Peru, a sector that “has experienced enormous growth in recent years, reaching a figure of 4.5 million tourists in 2020 [forecasts before the Covid-19 crisis].” There are tourists who come to Peru specifically to take ayahuasca. But there are others who travel for other reasons and, once there, hear about ayahuasca and decide to try it, Oblak stated.

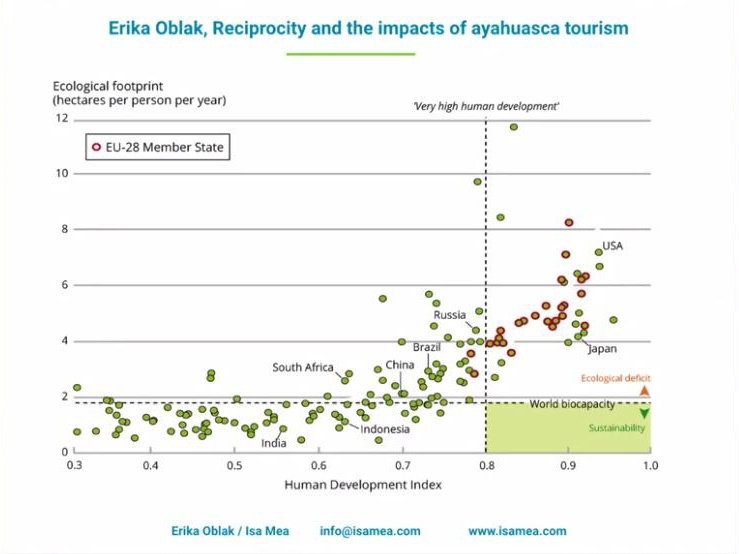

Oblak began her presentation with an eloquent graphic: “We should be in the green zone — low ecological footprint and some human development index — but no country is there. What is worrisome is that the countries we see on the left tend to move into the upper right quadrant, putting more pressure on natural resources. This means that places like the Amazon are becoming the target of corporations and other extractive businesses.” Oblak gave the example of the devastating impact that legal and illegal gold mining is having in areas such as Madre de Dios, which has a serious impact on the health of the rainforest and its inhabitants due to the use of mercury and other chemicals.

Mining also causes social havoc in the areas where it is conducted, bringing prostitution and violence to the jungle. Oblak revealed a terrible fact: the indigenous population makes up barely 5% of the total in the Amazon region but represents 25% of the victims of violence in the area, many of them related to the protection of their communities’ environment.

Impact of Ayahuasca Tourism

“Indigenous populations account for 5% of the world’s population, but their lands are home to 80% of the planet’s biodiversity. In contrast, our culture has destroyed more than half of the rainforest, decimated half of the vertebrates and more than 40% of the insects, just in the last 50-60 years. My question, when I see these numbers is, “What do they know that we don’t?” And the first thing I was taught when I started studying plants was, “Before you pick a plant you have to ask permission, and know how much you are allowed to take, and when you do you have to say ‘thank you’.” I get the feeling that our culture is not capable of saying something so basic like ‘please’ and ‘thank you’.”

The “sustainability” mentioned by Oblak refers not only to ayahuasca but to the entire plant and human ecosystem that surrounds it, “We must understand that, without the knowledge of the Indigenous people, the plant is just a plant. If we destroy the Amazon we are also destroying the knowledge about the use of the plant,” she explained.

“I believe that ayahuasca tourism can have a very positive impact if it is done in a responsible way. And I am not talking about responsibility from the mouth, but from the heart. Everyone involved in this activity should be equal: centers, Indigenous people and visitors. The centers can have a very important role in communicating what is happening in the Amazon, how this temple where ayahuasca grows is disappearing.”

“The ayahuasca centers are mostly run by foreigners, who do not live in Iquitos year-round, so the likelihood that the money they generate will leave the region is very high. These same foreigners are the ones who handle the marketing tools to contact our world, so they monopolize the best-paying jobs.” How can we move towards reciprocity in relations with Indigenous people? According to Oblak, “Moving from ‘me’ (my profit, my work, my healing) to ‘we,’ thinking what is good for the community: empowering local communities, giving them visibility, pushing for political change in your home country and, above all, changing your own lifestyle because that is the best thing you can do to preserve ayahuasca and the Amazon.”

Original talk:

Cover photo: “Segundo Feitio de Ayahuasca da Serra Sagrada”. Author: upslon.