General situation

International law

The Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971) subjects several psychoactive compounds contained in plant species to international control. DMT (N,N-dimetyltryptamine, a tryptamine alkaloid contained in Psychotria viridis and other plants generally used in the preparation of ayahuasca) is a Schedule I controlled substance in the Convention. However, according to the International Narcotic Control Board (INCB) Report for 2010 (par. 284) ‘no plants are currently controlled under that Convention […]. Preparations (e.g. decoctions for oral use) made from plants containing those active ingredients are also not under international control’.

There is no general consensus among judges and law enforcement officials on whether ayahuasca is illegal because it contains DMT, or not. It is up to national governments to make the final decision in their own jurisdictions on whether to impose controls on these plants and preparations, including ayahuasca.

National drug legislation

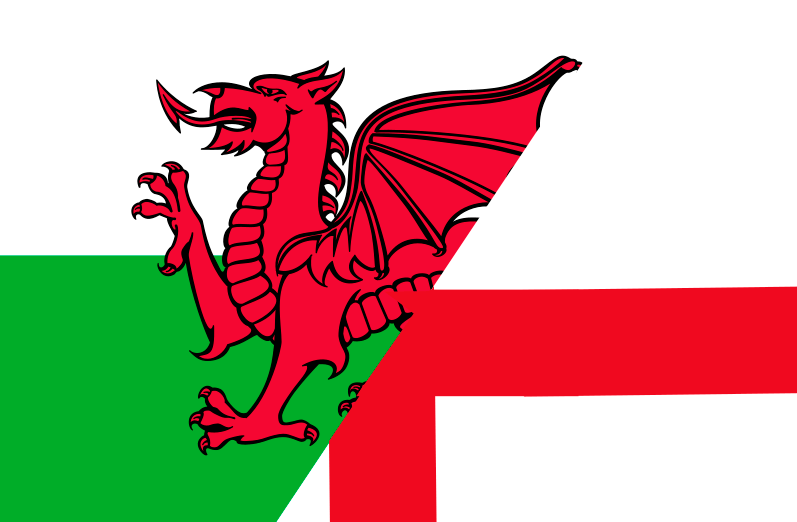

England’s primary instrument of drug prohibition is the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. If a substance is scheduled under this legislation, its possession, supply, production and importation/exportation becomes a criminal offence. Substances are placed in either Class A, B, or C, with Class A containing those substances deemed to pose the greatest risk of harm to self and others. Whilst ayahuasca is not scheduled under the Act – and nor are the plants it is typically constituted from – its psychoactive component, DMT, is scheduled as a Class A drug.

Possession of DMT can result in a custodial sentence of up to 7 years and any offence beyond possession (supply, production and so on) can result in a life sentence. It is worth noting that these statutory maximums would almost never be given in practice. For a more realistic impression of the sentences to be expected for Class A drug offences, see the Sentencing Council’s sentencing guidelines, Drug Offences: Definitive Guidelines.

The question then remains as to whether the fact that ayahuasca contains DMT means that it is captured by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Whilst case law has long since clarified that having a plant that naturally contains a psychoactive substance controlled by the Act does not suffice, there is a provision in the Act that provides that any preparation made that contains a scheduled substance would fall within its ambit.

To illustrate how this provision operates in practice, an analogy can be drawn with magic mushrooms, a species of which – the Liberty Cap – is native to England and Wales. Until 2004 the fungi itself was not scheduled within the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, although the psychoactive component it contains – psilocybin – was. Thus, being in possession of magic mushrooms did not constitute a criminal offence unless the mushrooms were deemed to constitute a preparation, resulting in lots of tortuous case law as regards what that might involve: Did drying them out suffice? Freezing them? and so on. In 2004 – largely as a result of concerns about importation of magic mushrooms from abroad – psilocybin containing fungi were themselves prohibited. An unfortunate distinction when it comes to ayahuasca, however, is that it is very difficult to argue that it does not constitute a preparation, being almost the definition of such: thus the plants that it consists of do not appear to need scheduling for the brew to fall squarely within the parameters of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

Even if it were to be successfully argued that ayahuasca does not fall under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, it would then unavoidably be caught by a recently passed piece of legislation – the Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 – that outlaws supply of all psychoactive substances, with a psychoactive substance defined as one which affects one’s mental functioning or emotional state. Note, this Act does not criminalize simple possession of such substances.

Cases

There is only one case where the legality of ayahuasca has been tested in the English courts: R v Aziz [2012] EWCA Crim 1063. Here the trial court took the view that ayahuasca constitutes a preparation containing DMT and thus is a Class A drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. Aziz tried to argue for a religious exemption from prohibition, utilizing Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects religious freedom. This was on the basis that he was a shamanic practitioner who had supplied ayahuasca in a ceremonial context. The trial court took the view that prohibition trumped religious freedom and declined to allow him such an exemption. In refusing Aziz leave to appeal on both of these points, the Court of Appeal were definitive in their view that “if a religious group, however well established, adopts as part of its rituals a deliberately unlawful act, the fact that this is part of a religious ceremony does not provide it with legal authorization”.

It is worth noting that members of an English Santo Daime church were arrested in the UK in 2010, with their ayahuasca seized, but the case was dropped in 2012 with the prosecuting body stating that there was insufficient evidence for a realistic prospect of conviction. The whole process was extremely costly for the group, both financially and emotionally. It is important to recognize that the abandonment of the prosecution does not mean that their status is currently legal.

Relevant documents

- Fax INCB 2001 Netherlands

- INCB letter ICEERS

- Hoasca 1971 Convention Legal Brief

- INCB Annual Report 2010

- INCB Annual Report 2012

- UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- TNI/ICEERS Ayahuasca Policy Report

- ICEERS Technical Report on Ayahuasca

- Plantaforma Ayahuasca Report Spain (Spanish)

- Declaration of Principles of the Religious Groups who consume the Tea Hoasca

Categories:

Countries

Tags:

legality

, ayahuasca

, map

, England and Wales